(Dr.) Barraud House Architectural Report, Block 10 Building IOriginally entitled: "A Brief Architectural History of the Dr. Barraud House"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series—1198

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

A BRIEF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY

OF THE DR. BARRAUD HOUSE

Architectural Research Department

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

July, 1988

A Brief Architectural History of the

The Dr. Barraud House

Situated on the northwest corner of Francis and Botetourt Streets, the Barraud House is one of Williamsburg's original eighteenth-century dwellings. This frame, one and one-half story house is also one of the best preserved houses in the Historic Area (Fig. 1). It retains much of its late eighteenth-century woodwork in the ground floor entertaining rooms and upstairs bed chambers. The interior and exterior cornices, raised-panel wainscotting, most of the window surrounds, panelled doors, and floorboards display characteristic late colonial detailing.

Until a thorough dendrochronological analysis of the Barraud House has been completed, we can only guess at the original date of its construction. It seems likely that the house was built in the 1760s or early 1770s either by William Carter, an apothecary, or blacksmith James Anderson, the subsequent owner of the property. A map of Williamsburg made by a French officer in 1782 confirms the presence of a squarish house standing on the site. As was common practice in Williamsburg at the time, Carter or Anderson probably rented the house to tenants rather than live in it themselves.

In 1785 Dr. Philip Barraud, a physician who worked at the Public Hospital and also served on the Board of Visitors at

Fig. 1. The Dr. Barraud House (photograph by Linwood Aron, March 9, 1943)

2

the College of William and Mary, purchased the house from Mrs. Susannah Riddle. During their occupancy, Dr. Barraud and his wife Ann made substantial changes to the house by constructing an additional ten feet to the western side of the house, rearranging the ground floor rooms, and installing some of the present eighteenth-century woodwork. Barraud later became the director of the Marine Hospital in Norfolk in 1799 and two years later sold his house in Williamsburg to Anna Byrd, a widow, who proceeded to use it as a boarding house.

Fig. 1. The Dr. Barraud House (photograph by Linwood Aron, March 9, 1943)

2

the College of William and Mary, purchased the house from Mrs. Susannah Riddle. During their occupancy, Dr. Barraud and his wife Ann made substantial changes to the house by constructing an additional ten feet to the western side of the house, rearranging the ground floor rooms, and installing some of the present eighteenth-century woodwork. Barraud later became the director of the Marine Hospital in Norfolk in 1799 and two years later sold his house in Williamsburg to Anna Byrd, a widow, who proceeded to use it as a boarding house.

Through much of the nineteenth century, the house served as a comfortable and spacious residence for various Williamsburg families who made very few architectural changes to the building. In 1924 Archie and Mary Ryland purchased the house and conveyed it to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1940 while retaining a life tenure to the residence. In 1942 the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation restored the building to its eighteenth-century appearance. Four years after Mrs. Ryland's death in 1983, the Foundation began the task of refurbishing the house as a special guest accommodation for members of the Raleigh Tavern Society.

Period I: ca. 1760s-mid 1780s

Like many buildings in Williamsburg, the Barraud House has a complex architectural history. The house has two distinct periods of growth, both of them occurring within a very short time of each other at the end of the eighteenth century. The 3 first building on the site was a relatively modest frame structure, measuring 37 feet along its Francis Street façade and 33 feet deep. Composed almost entirely of pine with a few pieces of poplar, most of the framing members of this first structure still survive enveloped within the present building. The framing, typical of colonial buildings in Williamsburg and Tidewater Virginia, is composed of large sills, corner posts, down braces, and wallplates and smaller studs and common rafters. The principal framing members are hewn, riven, and pit sawn and secured with mortise, tenon, and lap joints and pegged with wooden pegs known as treenails. one unusual feature about this framing is the composition of the common rafters. In order to span the 33 foot depth of the house and maintain a sharp 45 degree angle slope, the rafters had to be extraordinarily long. To obtain the required length, colonial carpenters spliced two separate pieces together near the apex of each rafter.

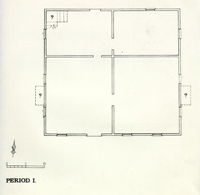

The front of the house probably looked much like the asymmetrical façade of the Moody House standing on the other side of Francis Street. The original plan of the house probably consisted of two front rooms and two smaller back rooms (Fig. 2). The front door remains in its original location and had two windows flanking it on the east and one on the west. However, it opened into a large room instead of a central passage. The raised panelled wainscotting that is now in the northwestern ground floor room probably adorned the west front room during this period. The original position of the chimneys is unknown.

PERIOD I.

PERIOD I.

Fig. 2. Period I plan ca. 1760s-1780s. (drawing by Carl Lounsbury based on Whiffen, 1988).

4

One possibility is that the two front rooms may have been heated by gable-end chimneys, but the two smaller back rooms were probably unheated.

The eastern back room was more than two feet shorter than its present size, measuring slightly less than 12 feet deep. The room was simply plastered at this time rather than wainscotted. Although the location of the original stair cannot be determined with any certainty, it did rise through one of the two western rooms, most probably toward the back of the house. Paint analysis suggests that most of the present eighteenth-century interior doors and architraves, exterior window architraves, and floorboards along with parts of the raised panelled wainscotting dates from this first period of construction. However, it seems likely that the house was originally far less ornamented than during the Barraud occupancy in the last two decades of the eighteenth century.

The original arrangement of the upstairs rooms is equally problematical. Depending on where the original stairs rose, there were at least three second floor bedchambers and possibly a smaller fourth one. More than likely the southeastern front bedchamber was heated by a fireplace and possibly a corresponding front bedchamber on the southwestern side as well. These upper rooms were lit by pedimented dormers on the south and north sides and by smaller six over six sash windows on the west and east gable ends.

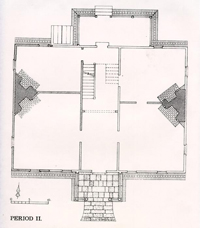

Period 11: 1785-1801 The Barraud Period

Shortly after its construction, the house underwent a series of changes that are still difficult to sort out completely. Suffice it say that increasing demands for larger entertaining rooms and a more formal, symmetrical façade arrangement resulted in the lengthening of the house 10 feet to the west and the introduction of a center stair passage (Fig. 3). This renovation took place sometime between 1782 when the Frenchman's Map shows its earliest form and 1796 when Dr. Barraud insured his property. The plat that accompanied his insurance policy described the building as a wooden dwelling 47 by 33 feet, matching its present configuration.

Recent investigations of the fabric of the building suggests that the changes were far more extensive than the simple addition of ten feet to the western half of the house. Dr. Barraud probably took the opportunity to enhance the appearance of the house with new woodwork and reorient the circulation pattern of the rooms. During this renovation, the chimney foundations and stacks were resited and completely rebuilt, creating two center, gable-end chimneys with corner fireplaces heating the four ground floor rooms. All the old floors were taken up and refitted. The original raised panelled wainscotting, which was probably in the front western room in the first period, was refitted and installed in the back western room. The west front room received new raised panel wainscotting. A new stair with turned balusters and molded

Period II

Period II

Fig. 3 Period II plan: The Barraud era. (drawing by Carl Lounsbury based on Whiffen, 1998).

6

handrail was installed in the newly created center passage. Windows were installed in the western addition of the house that nearly match the original fenestration and trim that was retained throughout the older part of the house.

The Barrauds also decided to paint the new woodwork installed in the remodeling. Apparently the somber dark gray of the Period I woodwork held little appeal. The woodwork in the two completely remodeled western ground floor rooms and new stair passage received a yellowish white coat of paint as did the new western chambers on the second floor. The two older eastern ground floor rooms were enlivened with a moderate greenish blue paint. This color was also repeated upstairs in the two eastern chambers. The early doors were painted a dark reddish brown as well as the baseboards and the door surrounds at the height of the vertical faces of the baseboards.

Period III: 1801-1942

In 1801 the Barrauds sold the house on Francis Street to Anna Byrd. Subsequent owners continued to alter the house in small ways to meet their changing needs over the next century and a half. Early in the nineteenth century a small enclosed room was added to the back of the house. Sometime later new porches were added to both the front and back of the house.

Among the most prominent changes inside the house was the replacement of the Barraud period stair in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century (Fig. 4). This stair was

Fig. 4.Center passage with late nineteenth-century stair and panelling. (photograph by Frank Nivison, 1941).

7

approximately in the same position of the earlier one and rose along the west wall of the center passage. The passage itself received narrow matchstick wainscot panelling at this time. Changes too occurred throughout the house as bathrooms and closets were constructed to meet modern demands of plumbing and storage. The northwest room was converted into a kitchen in the early part of this century, rendering the detached frame one behind the house redundant. However, the original eighteenth-century mantel in this room survived these changes. In 1942 it was renovated and moved from the kitchen to the front southeast room. The only other of the six original Barraud period wooden mantels that survived in the house was the one located in the southwest chamber on the second floor.

Fig. 4.Center passage with late nineteenth-century stair and panelling. (photograph by Frank Nivison, 1941).

7

approximately in the same position of the earlier one and rose along the west wall of the center passage. The passage itself received narrow matchstick wainscot panelling at this time. Changes too occurred throughout the house as bathrooms and closets were constructed to meet modern demands of plumbing and storage. The northwest room was converted into a kitchen in the early part of this century, rendering the detached frame one behind the house redundant. However, the original eighteenth-century mantel in this room survived these changes. In 1942 it was renovated and moved from the kitchen to the front southeast room. The only other of the six original Barraud period wooden mantels that survived in the house was the one located in the southwest chamber on the second floor.

Period IV: 1942-1987

When the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation architects renovated the house in 1942, relatively few changes were necessary. The stair in the central stair passage had to be rebuilt to replace the late nineteenth-century one, the walls were replastered, exterior weatherboarding was renewed, the chimneys were rebuilt, and the front and back porches were reconstructed based on architectural and archaeological evidence. A new kitchen with modern conveniences was built in the northeast room.

Before work on the Barraud House restoration began, inspection of the structure revealed that the existing Flemish 8 bond brickwork of the basement walls was in very poor condition and that replacement was inescapable. Accordingly, the house was shored up and entirely new walls constructed (Fig. 5.). Modern construction methods such as the use of steel beams and additional brick piers were employed to help stabilize and support the weight of the house. Ground-laid brick gutters, found surrounding a portion of the house during archaeological investigations, were reconstructed as well.

Like most early restorations in the Historic Area, the interior was stripped to its skeletal frame allowing the Colonial Williamsburg architects the opportunity to examine the structural integrity of the framing as well as trace historical changes in the fabric (Fig. 6). For example, when the paint was scraped away on the stair trim on the second floor, traces of the original baluster profile were discovered, which was copied and incorporated in the design of the reconstructed stair. Unfortunately, the wholesale removal of many of the earlier materials meant that the original wooden lath and lime plasterwork was destroyed in the process, replaced by modern metal lath and plaster and honeycombed with ducts and electrical wiring.

Because of the gradual changes that occurred in the 150 years between the Barrauds ownership and the 1942 restoration, some matching and replacement of original interior woodwork was required. Throughout the house, cornices, baseboards, and chair rails were patched and replaced where necessary. New mantels

Fig. 5.Shoring up the house and replacement of the foundation walls during the 1942 restoration. (photograph by Frank Nivison, February 5, 1942).

Fig. 5.Shoring up the house and replacement of the foundation walls during the 1942 restoration. (photograph by Frank Nivison, February 5, 1942).

Fig. 6.Ground floor rooms stripped of their plaster during the restoration. View from southeast room toward the stair passage. (photograph by Frank Nivison, July 30, 1941).

9

based on eighteenth-century mantels in Colonial Williamsburg's collection, were constructed and installed in three of the four upstairs bedchambers and the two ground floor western rooms. Although all the interior panelled doors that open into the passage survived as well as the rear door, the original front door had long since disappeared. During the restoration it was replaced by an eighteenth-century door taken from the neighboring Chiswell House. A nineteenth-century door that opened between the back northwest room and the front southwest room was closed off and modern panelling fabricated to fill in the gap in the wainscotting in each room.

Fig. 6.Ground floor rooms stripped of their plaster during the restoration. View from southeast room toward the stair passage. (photograph by Frank Nivison, July 30, 1941).

9

based on eighteenth-century mantels in Colonial Williamsburg's collection, were constructed and installed in three of the four upstairs bedchambers and the two ground floor western rooms. Although all the interior panelled doors that open into the passage survived as well as the rear door, the original front door had long since disappeared. During the restoration it was replaced by an eighteenth-century door taken from the neighboring Chiswell House. A nineteenth-century door that opened between the back northwest room and the front southwest room was closed off and modern panelling fabricated to fill in the gap in the wainscotting in each room.

One significant change occurred in the passage where the Colonial Williamsburg architects installed an elliptical arch separating the front of the passage from the back stair section. Based on a liberal interpretation of certain markings on the early floorboards and by evidence on the cross beam, they reconstructed an elaborate arch based on precedent found in other houses in the Historic Area such as the Wythe and Bracken Houses.

The most significant changes that occurred on the exterior of the building during the 1942 restoration was the replacement of nineteenth-century siding with modern beaded weatherboards, the removal of nineteenth-century porches on both the front and rear of the building, and the construction of new porches. The outline of both porches was based on architectural and archaeological evidence (Fig. 7). The architectural detailing of the Chinese Chippendale railing and slender porch

Fig. 7.Removal of the nineteenth-century front porch during restoration revealed the outline of the earlier smaller porch. (photograph by Frank Nivison, 1941).

10

columns on the front porch was based partially on academic sources, most notably plates from Abraham Swan's A Collection of Designs in Architecture (1757), and from the porch at Battersea in Petersburg, now dated 1824. Like the interior stair arch, this design is probably rather more fanciful than what would have been constructed in the Barraud period during the 1780s and 1790s (Fig. 1).

Fig. 7.Removal of the nineteenth-century front porch during restoration revealed the outline of the earlier smaller porch. (photograph by Frank Nivison, 1941).

10

columns on the front porch was based partially on academic sources, most notably plates from Abraham Swan's A Collection of Designs in Architecture (1757), and from the porch at Battersea in Petersburg, now dated 1824. Like the interior stair arch, this design is probably rather more fanciful than what would have been constructed in the Barraud period during the 1780s and 1790s (Fig. 1).

Period V: 1987-1988 Renovations

In order to accommodate the needs of a guest residence for members of the Raleigh Tavern Society, the Barraud House underwent several changes in 1987-1988. Among the architectural changes was the introduction of new lighting, heating, air conditioning, and ventilation systems. In addition, the 1942 kitchen in the northeast room was renovated with modern appliances on the second floor, a few bathroom and closet walls constructed in 1942 were slightly rearranged and a new door installed where a nineteenth century door had been cut through between the northeast and southeast room in order to incorporate the requirements of the two new bedroom suites. Little, if any, original fabric was disturbed at this time.

In an effort to answer many of the outstanding questions about the origins and development of the Barraud House, architects and architectural historians at Colonial Williamsburg employed two relatively new tools of investigation. we have begun the process of determining the various ages of the house 11 framing members through dendrochronology, the scientific study of tree ring samples. By carefully drilling into several original framing members, core samples are taken from throughout the house (Fig. 8). These samples are then taken back to a laboratory where they are subjected to microscopic and computer analysis to determine their ring growth pattern. Once similarities of ring growth are noted among the samples, they can be compared with chronologically known patterns and crossdated to a precise year. This then will tell us the year that the framing members were felled in the forest.

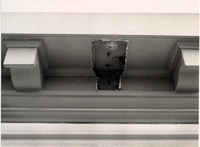

In addition, systematic paint analysis has revealed successive layers of colors that had been applied to the woodwork and serves as another aid in determining the chronological sequence of changes that occurred in the house during the late eighteenth century. Like dendrochronology, paint samples are taken from various locations and then subjected to microscopic analysis to determine sequences of layers and the identification and composition of paint pigments. A close study of paint layers from the exterior cornice, for example, reveals that it was originally painted white (Fig. 9). As mentioned previously, the earliest paint layer found in most of the ground floor rooms and second floor chambers was a dark gray. Some rooms have received as many as nine coats of paint between the Barraud period and the 1942 restoration.

Although not as spectacular, renewed on-site investigation of the house has also helped in determining

Fig. 8. Dr. Herman Heikkenen of the American Institute of Dendrochronology taking wood samples from a down brace for dating analysis. (photograph by Carl Lounsbury, July 1987).

Fig. 8. Dr. Herman Heikkenen of the American Institute of Dendrochronology taking wood samples from a down brace for dating analysis. (photograph by Carl Lounsbury, July 1987).

Fig. 9. Removal of a modillion block from the exterior front cornice revealed several paint layers. (photograph by Tom Taylor, July 1987).

12

structural changes as well as set the context for the two scientific studies. The renovations of the Barraud House in 1987 has enabled us to answer many of the outstanding questions that had puzzled earlier researchers. However, like most old dwellings, one good answer only creates a dozen new questions. Many puzzling aspects of this building's early architecture still allude us.

Fig. 9. Removal of a modillion block from the exterior front cornice revealed several paint layers. (photograph by Tom Taylor, July 1987).

12

structural changes as well as set the context for the two scientific studies. The renovations of the Barraud House in 1987 has enabled us to answer many of the outstanding questions that had puzzled earlier researchers. However, like most old dwellings, one good answer only creates a dozen new questions. Many puzzling aspects of this building's early architecture still allude us.